But why settle for a case in point when you could have three? A trio of new albums—though wildly dissimilar in sound—have a shared conceptual thread: Each one of them engages with traditional sounds in order to speak eloquently and passionately to the grimmest contemporary realities. They prove how even musical genres steeped in tradition (jazz, country, and Afrobeat, respectively) can bring moral bearing to in-the-moment plight; these albums resonate not only because they are unflinchingly topical, but also because they are deeply rooted in shared history and popular imagination.

Certainly, the music of Kamasi Washington teems with history. For the saxophonist/bandleader, every album is a chance to make an epic—whether through his triple-length debut, his conceptually-loaded Harmony of Difference EP, or his new Heaven and Earth, a double album that wears its grandiosity within its title. This latest opus feels big, and not just because its two halves each amount to more than an hour of music, individual songs generally clocking in at somewhere near 10 minutes, all of them decked out with choirs and strings, small-group improvisation breathing fire through large-ensemble motifs.Washington’s music feels epic because everything within it is writ large. Heaven and Earth’s dichotomous construction bears witness to the world as Washington sees it (the Earth half) and the transformed, kingdom-come world of his most righteous imagining (that’s Heaven). Thus, the album’s opening act is all about tension; the first song, “Fists of Fury,” adds new lyrics to an old Bruce Lee theme, and considers historic moments in which it becomes necessary to fight back against injustice. In the song, human agency is an implement of divine reckoning—a way to make things right in a world that so often feels like it’s gone wrong. The Heaven disc, by contrast, offers peace, perspective, and transcendence: Opener “The Space Traveler’s Lullaby” zooms out for a moment of Zen, while songs like “The Psalmist” and “Show Us the Way” seem like they’re pulling heaven downward into our ash and clay.

If those last two song titles feel significant, they are; religious tropes are integral to Washington’s music, and the psalm of lament/psalm of ascent structure of Heaven and Earth can’t help but recall the intercessory intentions of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme—a record famously imagined as a love song to the divine. And that’s just one of several ways in which Washington grounds his music in signs and signifiers from our shared past. He also festoons Heaven and Earth with relics and mile-markers from soul and R&B traditions—note the breezy string, conga, and wind-chime arrangements on the aforementioned “Fists of Fury,” a song that’s half kung-fu movie and half Curtis Mayfield anthem.

The album is saturated in the sounds of the Civil Rights era and its aftermath, as well as jazz at its most Afrocentric and politically motivated—and that’s not merely a stylistic decision. It’s ideological scaffolding for Washington’s songs. He’s deliberately putting us in the headspace of music that beats the drum for justice even as it appeals to a higher power for freedom and jubilee. It’s as if he’s reminding us that the story he’s telling is as old as time itself: To paraphrase an old U2 lyric, we’ve always had to dream up the world we want to live in; to bring heaven to earth through bent knees and fists of fury.

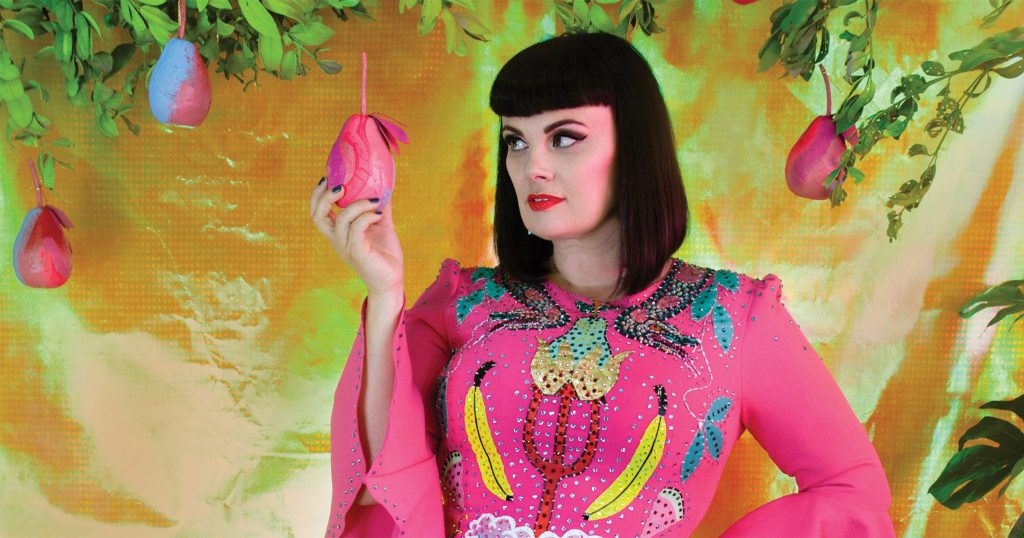

For a record that’s totally dissimilar in sound, yet comparable in how it uses traditional grammar to diagnose the present, consider Sassafrass!, new from country-soul belter Tami Nielson. It’s quite a bit more compact than the Washington album, yet in its own way it may be just as ambitious: Neilson pledges allegiance to roots music but offers an expansive definition of what exactly that includes. A powerhouse vocalist who can aim for the rafters without ever compromising her precision or control, she burns up a couple of vintage R&B tunes (“Stay Outta My Business,” which might have fit in on an Amy Winehouse album; “Miss Jones,” an in-the-red rave-up that pays tribute to the late Sharon Jones), but also croons her way through the supper-club sway of “One Thought of You,” and hits more conventional country storytelling in “Diamond Ring.” There’s even a bit of exotica here in “Bananas,” a song that filters late-50s exotica through Vegas razzle-dazzle, a high-and-lonesome pedal steel connecting it back to roots music.That last song also provides a window into how Neilson’s songs use retro sounds to address contemporary concerns; ostensibly a rejoinder to “tomatogate” (in which an influential country radio programmer offered dubious justifications for why women remain underrepresented in Nashville), “Bananas” tosses off one fruit-filled double entendre after another: “Bananas here, bananas there/ Seems it’s nothing but bananas everywhere,” Neilson winks; it’s one of the most blistering indictments of the wage gap you’ll hear anywhere, largely because it’s got the best jokes. Other songs have a similar topicality—“Smoking Gun” taps into the #metoo movement with its tale of casting-couch abuses, while “Stay Outta My Business” laments how working moms are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. And yet, Neilson’s use of tried-and-true musical idioms suggests that these songs aren’t really topical at all; that any one of them could have been ripped from this morning’s headlines or written 50 years ago.

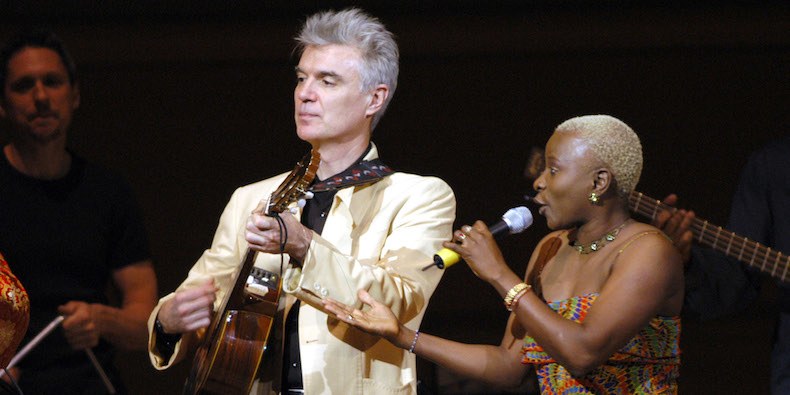

Finally, there’s Remain in Light, from the legendary Beninese singer Angelique Kidjo—a song-for-song remake of the benchmark Talking Heads record from 1980. That Brian Eno-produced classic was inspired by the sounds of Afrobeat, but mediated by pop flair and art-rock sensibilities. Kidjo’s remake takes these songs all the way back to their roots, stripping away any academic remove in favor of fiery Fela Kuti grooves—including horn accompaniment and rolling polyrhythms from the great drummer Tony Allen. The immortal “Once in a Lifetime” sizzles with brass firepower; “The Overload” scales things back and lets the low-end do the heavy lifting, to suitably ominous effect.Kidjo, in other words, isn’t just engaging with traditions—she’s reshaping an already-venerated body of song. Much could be said about her album as an act of cultural reclamation—about how she makes the original album feel almost like a half-measure—but the most striking thing about her album is how embodied it feels; by swapping David Byrne’s robotic funk for something more visceral and gritty, she also shifts the meaning of his lyrics. What once scanned as paranoid political hallucinations (albeit well-founded ones) now feel like anthems from someone who’s deep in the shit, retelling these tumultuous stories as lived experiences. Byrne’s “Listening Wind” felt like a spooky reflection on colonialism, while Kidjo’s lands like a gut-punch reminder of how gentrification keeps the colonial tradition alive. And where Byrne’s reading of “The Great Curve” considered femininity in the abstract, Kidjo brings to it a kind of lived-in physicality.

Like Washington and Neilson, Kidjo is remaking history, even as she proves that—as Faulkner wrote—the past is never really past; she meets our times head-on, with songs of experience that bring moral heft and clarity, and prove themselves imminently adaptable to a strange new world that probably hasn’t changed as much as we’d like to think.