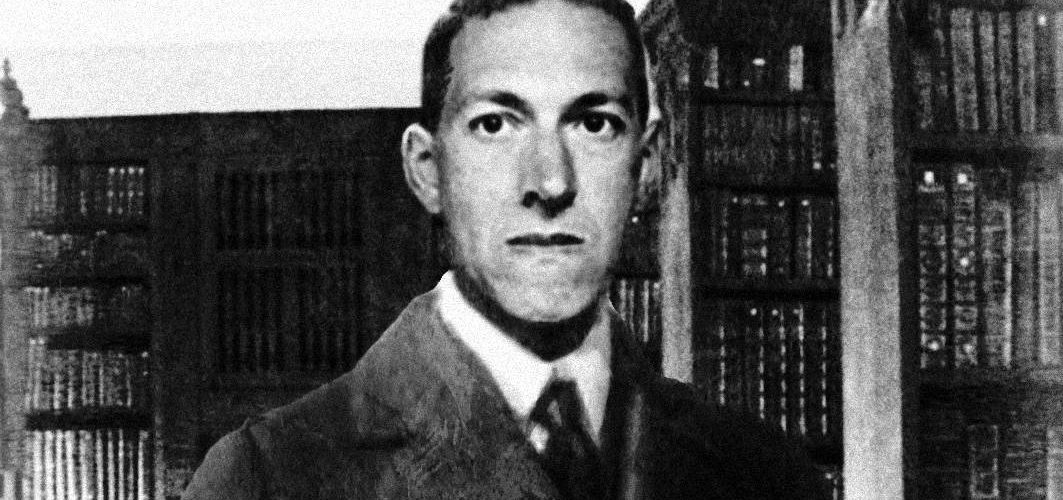

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.” — H. P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu

While there are many strains of horror, from slasher flicks to zombie films, from creature features to psychological horror to gore fests, there are none that frighten me on any level so much as the Cosmicism of H.P. Lovecraft. I recall not being able to sleep the night I saw my first horror film, Jaws. And having nightmares for weeks after watching my first supernatural horror film, The Amityville Horror. But while physical and psychological/supernatural scares are frightening, what I find terrifying about Lovecraft and Lovecraftian horror is that is has become a basis around a philosophy that does not exist just in the pages of books or images on a screen, but has become a driving force in the world around us. But in the spirit of something director Scott Derrickson (Doctor Strange), who cut his teeth making horror films once said, “If you scare me, I’ll fight your ass until you scare me no more,” I want to highlight my 5 favorite films inspired by Lovecraft and explore a bit of Cosmicism and its influence.I say inspired by Lovecraft because while his popularity has grown in magnitude over the last few decades, there have been few direct adaptations of his work on the screen. Nonetheless, he has been a direct inspiration on authors including Stephen King and Neil Gaiman, film writers and directors like Guillermo del Toro, Stuart Gordon, and John Carpenter, and countless fans and followers. Lovecraft’s influence can be felt in Batman lore (Arkham Asylum being named after Lovecraft’s fictional town of Arkham, Massachusetts); the Necronomicon, a fictional book of dark magic, which has become a staple in horror, fantasy, and science fiction genres; Cthulhu, a giant, humanoid, tentacled “Great Old One” who has become part of the common lexicon, the subject of countless memes, and essentially the character design for Davy Jones in Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean films; and in wider culture, the philosophical movements of Cosmicism and Speculative Realism.

It’s exceedingly difficult to pinpoint the influence of any writer or their ideas at any specific point in time. There are so many factors involved. Their ideas can come to people creating new art and fans ingesting their work directly or through intermediary sources. Some will take ideas from the author that were intended. Some will take ideas they perceive from the work that weren’t intended by the author. Some will apply the influence back into books and film and theater and music. Some will apply it to philosophy or religion or politics.

For example, the neoreactionary movement, a political philosophy that has roots in libertarianism but also advocates for a return to elements on monarchism and includes strains of white supremacist thought is commonly referred to as the “Dark Enlightenment.” That name comes from Nick Land, an English philosopher, whose The Dark Enlightenment serves as a manifesto for the movement. And it’s hard not to draw some connection between Land’s “Dark Enlightenment” and Lovecraft’s “new dark age,” especially as Land often cites Lovecraft as an influence and has begun writing psychological horror stories himself. Neoreaction has in the last few years gone from an entirely fringe movement to something more substantial as those tied with its philosophy have come to the forefront of culture, becoming an influential school of thought among the alt-right and proponents like tech mogul Peter Thiel, computer scientist Curtis Yarvin (who writes under the pseudonym Mencius Moldbug), and pundit Steve Sailor finding greater appeal in wider culture.

Lovecraft’s racism and views on white supremacy dovetail nicely into elements of the neoreactionary and alt-right movements. As does his Cosmicism, a dark and cynical view of existence that places humankind as an entirely insignificant element of the vast universe and the horrors that lurk in and beyond it. But while Lovecraft’s imagination solidified this view of being into a framework that others have built upon as a way of approaching life, it has also inspired filmmakers who have shaped works inspired by his stories that ask us questions about who we are and who we want to become in the face of an often unforgiving and perplexing universe.

Here are, in my estimation, the five best films inspired by Lovecraft and his work:

- Alien

Alien transcends its primary genres, science fiction and horror, becoming a story of female empowerment and the spirit of mankind in the face of unrelenting evil. Featuring an outstanding cast including Tom Skerritt, Harry Dean Stanton, John Hurt, Yaphet Kotto, and Ian Holm, it launched Sigourney Weaver as a star actress and became a touchstone of director Ridley Scott’s career. Spawning a long string of sequels and prequels and tie-ins, Alien perfectly captures the atmosphere of much of Lovecraft’s work: an uncaring killing machine who views humanity as nothing so much as an insect or base elements to reproduce, set across the backdrop of infinite space.

- Re-Animator

The only direct adaptation of a Lovecraft story on this list, Re-Animator is a darkly comic story of a doctor and researcher, Herbert West, who discovers a formula that can re-animate the dead. In Jurassic Park, Jeff Goldblum’s character, Dr. Ian Malcolm, famously quips, “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” Re-Animator’s Herbert West, in the tradition of Dr. Frankenstein, not only doesn’t bother to ask if he should, but is convinced he should – to the point where one finds oneself cheering for him out of a sense of pity mixed with amusement – as he combats the pure evil he has unleashed. But this is dangerous territory, because West is no hero, and in his singular drive to re-animate life, he destroys it at every step.

- Event Horizon

Directed by Paul W.S. Anderson, who later rose to fame with the Resident Evil franchise, Event Horizon is another film set in space as a rescue ship attempts to salvage another ship who was testing a device that bends space in order to travel immense distances in mere seconds. The experiment was a failure – of immense proportions – and had transported the ship and crew to another dimension, a kind of hell, and the rescue crew becomes engulfed in a fight for survival against what has returned with the ship, along with what may be something even more horrific: the demons that haunt the mind and heart and soul of the man who designed the experimental ship.

- The Thing

Much of director John Carpenter’s film oeuvre owes a debt to Lovecraft. From Halloween, which embodies an inhuman, uncaring force in the individual of Michael Myers, to In the Mouth of Madness, which follows an insurance investigator trying to track down a missing horror novelist, Carpenter mines the depths of Lovecraftian horror like few other storytellers. The Thing, like Alien, pits a secluded group of individuals dealing with an inhuman being who cares not a whit for the sacredness being human. But it also asks questions about how we treat each other in the face of terror and how can we trust each other when our own hearts are dark, scared, and lonely.

- The Cabin in the Woods

Co-written by Joss Whedon, The Cabin in the Woods’ playfully infuses everything from zombies to ghost-like creatures in its genre twisting story of a group of young people camping in the woods. Its “big bad” though is right out of Lovecraft, a clear play on his “Old Ones.” It actually manages to be legitimately funny in many places while also tackling bigger questions about what humanity is capable of inflicting on itself in the name of “the greater good” and the courage to treat others with dignity and respect for life and individual agency in the face of great, uncaring forces. As Harper Lee wrote in To Kill a Mockingbird, courage is “when you know you’re licked before you begin, but you begin anyway and see it through no matter what.”