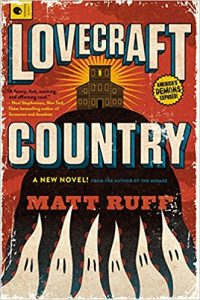

Illustration by Seth T. Hahne

“I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids- and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in a circus sideshow, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination- indeed, everything and anything except me.” – Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

“Nor did they seem especially alien to her, the main difference between them and other rich, self-important white people she had encountered being their willingness to converse with her. About necromancy. But even the talk of magic wasn’t that peculiar, for most of them spoke of it as they would of money, or politics, or any other means of bending the world to their will.” – Matt Ruff, Lovecraft Country

Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country reads like a narrative rendering of a serial television show. He had begun writing the story with that very medium in mind. Something akin to The X-Files. It is not surprising then that the book has been picked up for that very purpose under the creative direction of Jordan Peele (Get Out, Key & Peele) and Misha Green (Underground, Helix) for HBO. The structural elements of the book rely heavily on what appears to be an intentional drive towards centering his story on heroes that would not find representation in these types of genre narratives.

Beginning this book, skepticism is easy when looking at the odds of success for a white, male author writing a story about a black family that does not devolve into the same tropes and clichés that horror and science fiction fare tends towards when addressing minority characters: the numerous “magical negroes” of Stephen King (and other writers), the tokenism and death count of minorities in slasher films, the othering of minorities through monstrous representation like The Creature from the Black Lagoon or King Kong, etc.

Beginning this book, skepticism is easy when looking at the odds of success for a white, male author writing a story about a black family that does not devolve into the same tropes and clichés that horror and science fiction fare tends towards when addressing minority characters: the numerous “magical negroes” of Stephen King (and other writers), the tokenism and death count of minorities in slasher films, the othering of minorities through monstrous representation like The Creature from the Black Lagoon or King Kong, etc.

Incorporating Howard Phillips (H. P.) Lovecraft in the title and at various points in the novel was also a potential minefield for slipping into narrative “othering.” Lovecraft has become one of the most celebrated American horror writers of this current age. His influence is quite literally ubiquitous within the horror community which–Surprise! Surprise!–is still largely made up of a white demographic. This is relevant because Lovecraft’s legacy is anything but friendly to minorities. Many of his stories, including “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”–a structural touchpoint for Matt Ruff in writing the novel–could be read as disguised arguments for his racist ideologies. “Shadow” could easily be seen as a cautionary tale about the dangers of miscegenation–the interbreeding of races.

Jason Sandford gives another example of Lovecraft’s underlying white supremacy in his exploration of Lovecraft’s controversial oeuvre:

“’The Horror at Red Hook’ is both one of Lovecraft’s most well-known stories and one of his most racist, with Lovecraft describing Aryan civilization as being all that stands against the ‘primitive half-ape savagery’ of lesser races.”

This is not to forget his more blunt expressions of racism, like a 1912 poem he wrote entitled, “On the Creation of N*****s.” A piece of writing referenced by title in Lovecraft Country much to the a chagrin of Atticus, one of the novel’s main characters:

“When, long ago, the gods created Earth

In Jove’s fair image Man was shaped at birth.

The beasts for lesser parts were next designed;

Yet were they too remote from humankind.

To fill the gap, and join the rest to Man,

Th’Olympian host conceiv’d a clever plan.

A beast they wrought, in semi-human figure,

Filled it with vice, and called the thing a N****r.”

Much of Lovecraftian mythology, if viewed through the lens of its author, could be considered a grand, fantastical representation of the fears of a white populace. White protagonists come up against creatures and beasts that are “inferior” to them–terrifying and disgusting in their form and primitive in their desires and motivations–and either become the other or attempt to control the other to accomplish their own ends. With merely a casual recollection of American (or, really, world) history, these patterns of human nature should be recognizable.

Nonetheless, Ruff’s book succeeds in subverting those Lovecraftian ideologies by planting the book’s points of view squarely with the black family at its center. The narrative’s white characters are both active and passive antagonists–in both banal and supernatural ways–within a realistic depiction of race and class in the 1950s. The world Atticus Turner and his family inhabit is largely alien to them because of the landscape’s general whiteness. The normativity of a white majority is largely deconstructed by making their whiteness monstrous and other. We are forced to see this world through the witness of black people who have their own lives, dignity and aspirations apart from their white counterparts.

Each chapter focuses on a specific character as they navigate this, still, familiar cultural milieu. White readers may find themselves given the opportunity to see the world from the perspective of those whose experience we often malign. Ruff dresses up these social ills in a variety of supernatural clothing–from ghosts to alternate dimensions to possessed voodoo dolls–and gives flesh to the unseen terror of racism that the black community experienced–and continues to experience to this day. These experiences are often conspiratorialized by white people in order to avoid their own complicity and guilt.

Each chapter plays out like a weekly vignette from The Twilight Zone or The X-Files, bookended by a story thread that weaves throughout the whole narrative involving sorcery, a cult called the “Sons of Adam,” and the usage of a “magic circle” which has a long history within the realms of horror and science fiction with the likes of Lovecraft & Dennis Wheatley. Caleb Braithwhite, the book’s central villain, seeks to utilize the Turner family to attain secret, supernatural knowledge and power. Thereby incarnating in the story what was only implied by the “magical negro” tropes in the genre’s past.

Ruff intentionally begins many chapters with an historical document or quote that foreshadows the sociological conflict inherent within each chapter. For instance, in the chapter entitled “Dreams of the Which House,” Ruff begins it with a segment from the “Standard Form, Restrictive Covenant” which was a document drawn up in Chicago in 1927 by the city’s real estate board to limit the terms of property ownership by black people. Within the scope of the chapter’s narrative, one of the main characters, Letitia, comes into some money mysteriously and decides to buy an old, large house in a largely white part of town in order to open up a boarding house. Ruff plays out this historical oppression within the chapter by showing some of the hoops Letitia must jump through in order to purchase the house and what happens when her white neighbors realize by whom they are living. Each story finding its existential dread less in the supernatural elements and more imminently in the travails of blacks getting through a day in America.

As someone who lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the recognition of the black narrative of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riots–an act of terror that citizens of Tulsa, themselves, often are not even aware and the black community continually fights to have the facts recognized–is front and center in the chapter entitled “The Narrow House.” Each chapter gives depth and character to the Turners and their kin. This is done by showing how the legacy of white transgression against black individuals and communities has given the characters a strength and dignity that has come out of oppression. Ruff gives each character their own struggles, large and small–never minimized–in order to make them into characters that have their own desires and self-possession instead of playing second fiddle to the needs and desire of white people.

And this is just two chapters of a book that follows a trajectory of exploring the horrors of racism and how the black community was forced to rely on each other in light of a reality that only allowed them to benefit whiteness–while their livelihood and communities remained suppressed. It remains a perennial practice for white people to believe conspiracy theories like the Illuminati, and Lovecraft Country presents a horrifying conspiracy of white, Lovecraftian cultists who aim to conquer the world. While the surface of this concept is imaginary, Ruff draws enough real parallels to actual history to show that white people are not that far removed from those same designs–whether conscious of it or not. Yet this continues to be the one theory white people, collectively, have refused to give credence.

Lovecraft Country is so compelling because it is able to weave the story into an allegory of race relations in America by utilizing pulpy science fiction and horror tropes to recast the world through the eyes of the black community. If white people are paying attention, they might get a glimpse into a horrific vision that the black community has been passing down for generations now against their will. These actions are still not gone from the world today, they have just been made more subtle. Racism is in the fine print instead of a large sign over a water fountain. Ruff reminds readers that the recent past has not gone away and that its ghosts continue to haunt the present. Instead of blatant legal constraints placed on the ability for African Americans to vote, we find politicians gerrymandering districts in order to dissect the demographics in their own favor. Or instead of Jim Crow extortion of freed sharecroppers, we exploit the labor of a disproportionate African American prison population for state and federal benefit–a normal pay rate being less than a dollar an hour for hundreds of millions in state industrial revenue.

It is no surprise then why Peele and Green would option the story for HBO after the critical praise both Get Out and Underground have received. The novel speaks to something very present and visceral that the majority population of this country, myself and the author are included in, often turn a blind eye towards in order to maintain our privileged place in society. Just as Harper Lee gave her generation a venerable and just “great man,” Atticus Finch, Matt Ruff has reshaped that image and given this generation a new Atticus. One that no longer needs a white man to argue his case, but one that demands that he and his family’s voice be heard in their full timbre and on their own merit.