The initial run of Will & Grace spanned the golden years of NBC Thursday night Must See TV evening comedies, from 1998 to 2006. It’s final season seems to have marked the end of that era, as NBC comedy programming never really recovered from the loss of its major properties. With Will & Grace, Friends, and Frasier all signing off within a few years of each other, the triumvirate of sitcom programming that ruled weekly TV ratings for a decade would never be replaced. It’s interesting, then, in the current cutthroat climate of network sitcoms, to see a throwback to NBC’s glory days make its way back to the small screen virtually unchanged from its heyday. That is in fact both the feature and the bug of this reboot; it appears to be frozen in time.

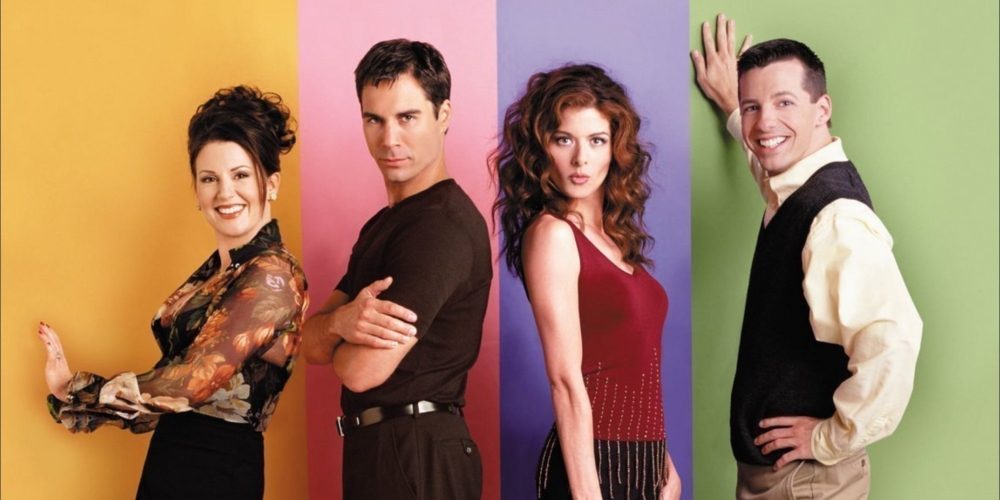

The weird, unsettling thing I can’t seem to get over with this new incarnation of Will & Grace is that it never missed a beat. Even the title pair, Will (Eric McCormack) and Grace (Debra Messing), appear to have barely aged at all since the show went off the air. Have they been vacuum sealed in formaldehyde for the last decade? It’s as if the show has been going on for the last ten years but the episodes were secreted away in a hidden bunker and they’ve just begun televising it again. Everything about the show screams 1990’s sitcom. I’m almost jarred by the fact that it’s not sandwiched between new episodes of Friends and Frasier.

In that sense, watching Will & Grace feels more like watching a documentary than a comedy. The jokes make me wonder how the show would even exist if Trump wasn’t president. His name should probably be in the credits for all the screen time he gets. But other than the updated jokes, the show mainly serves as a touchstone to show how far things have come since it was originally on the air. There’s the obvious comparison, which is to show how far gay rights have come. Will explicitly makes this point in the second episode of the season, “Who’s Your Daddy,” to a much younger man that he attempts to date. He specifically references the Stonewall Uprising which his young date (several decades his junior) is a little unclear on. When his date asks Will if he’d rather have sex or deliver a lecture, Will chooses the lecture. Will launches into an impassioned diatribe about how easy gay and lesbian youth have it today, standing on the shoulders of the two generations before that fought since Stonewall to secure the rights they have today. His date, thoroughly turned off by the boner-shrinker history lesson, leaves.

It’s nice to see pop culture reflect upon how quickly the world changes now. It’s been almost 50 years since Stonewall, but gay rights seem to have really hit critical mass only in the last ten, to the point where a show about a gay lawyer living in New York with his straight female bestie seems almost quaint. A modern version of Will & Grace might feature a trans woman living in a polyamorous group of four with another dude to play the, ahem, straight man. What was groundbreaking in 1998 seems pretty ho-hum now. Perhaps that makes Will & Grace a victim of its own success. While we are certainly a long way from universal acceptance of LGBTQ citizens in America, we’d be foolish to ignore the fast progress made in the last decade and more foolish still not to recognize the roll pop culture played in creating this more inclusive culture. Will & Grace were on the front lines of that pop culture revolution.

There’s another level to the documentary feel of Will & Grace that has nothing to do with sexual orientation and everything to do with the evolution of the sitcom as a genre and performance piece. Comedies have changed radically in the last decade. Comedies like Curb Your Enthusiasm, VEEP, Community, Parks & Rec, and Brooklyn 99 are an evolutionary step forward from the tried and true formula NBC ran with in the 1990s. It’s a little bit like trading in my Chevy Malibu for a horse and buggy to go from modern comedies, which feature neither a live studio audience nor a laugh track prompting me to know when I’m supposed to be more entertained. Modern comedies also seem to flow a lot better. Will & Grace is a serial offender of the “park and bark” crime, where a character stops, issues a joke, waits for the crowd to laugh, and then continues. It’s wildly unnatural, since people don’t usually stop talking in the middle of a thought or sentence to wait for someone to laugh before continuing. It’s not something I really noticed until seeing it in such stark relief. It makes me take a second look at comedies like Big Bang Theory, which is probably the worst modern offender here (Two Broke Girls comes to mind as well). On the opposite side of that coin, I also want to reconsider a show like Scrubs, which now looks even more like a gamechanger to have aired in 2001 but, stylistically, easily fits in with contemporary comedies, especially in its willingness to be dark and serious rather than portraying the world as a relentlessly positive place.

And so, I have to wonder if Will & Grace belongs on TV today as anything other than a nostalgic curiosity. It’s like rummaging through a box of your old things only to spend an unplanned hour reading through your old high school year book before packing it away for another decade. Nostalgia TV viewing can burn out hot and fast unless the show being brought back to life has a new spin on it. Having said all that, do I think the show is funny? Yes. It leans heavily on the comedic acting chops of the four main actors to deliver what is otherwise an uninspired, recycled set of jokes, and almost every episode’s plot revolves around shoehorning in some past character or major event from the show’s previous run. But despite all that, I laughed when prompted.

My hope for the next season is that the showrunners decide to be bold and try something new with the show – do more than just update it with more relevant jokes, update it with more relevant storytelling. Instead of showing us how much the characters haven’t changed, maybe allow them to change, and thereby reflect how much their audience changed while they were away.